War, peace and transformation in new South African fiction, with David Medalie (chair), Imraan Coovadia, Karen Jayes, Steven Boykey Sidley and James Whyle.

Session 12, Sunday 2 September, Market Theatre.

KARL VAN WYK

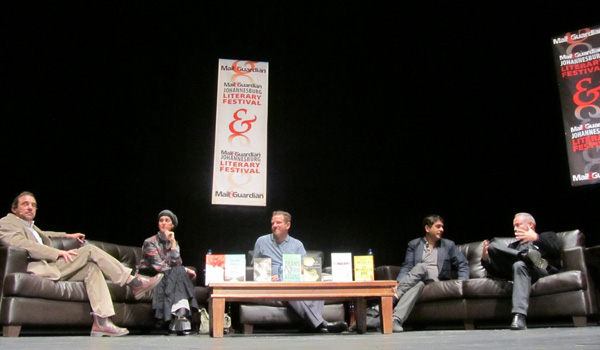

The panel: James Whyle, Karen Jayes, David Medalie, Imraan Coovadia, and Steven Boykey Sidley size up the audience, and each other

The twelfth session of the Mail & Guardian Literary Festival began with an apology by Darryl Accone, organiser-in-chief of the event. Based on the number of bookings for the session, more audience members should have been in attendance. Accone attributed the relatively poor outcome to Jan Smuts Avenue being closed off because of a concurrent festival, Jazz on the Lake, and this may have prevented people coming from the north arriving on time at the Market Theatre. However, the session proved to be a surprisingly lively event despite the poor turnout.

Academic and fiction writer David Medalie, who chaired the session, began by introducing the panel, which included novelist and writer of stage and screenplays, James Whyle, first-time novelists Karen Jayes and Steven Boykey Sidley (who prefers to be called Boykey), and Imraan Coovadia, who has quickly established himself as a relevant and original voice in South African literature, both in fiction and academia.

James Whyle says he uses his skills as a TV writer to create sequences weaved into a longer narrative

Whyle initiated the discussion by speaking about how his novel, The Book of War, was the product of an MA in creative writing at Stellenbosch University under the supervision of Marlene van Niekerk. I found it difficult to follow Whyle at some points as his sentences seemed to be made up largely of fragments and afterthoughts, with every sixth word or so punctuated by an ellipsis, creating pauses that sometimes awkwardly went on for far too long. However, he did make it clear that, when asked about the difficulties of writing historical fiction, his literary inspirations were Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, and, as perhaps a reaction against her, Hilary Mantel, whose books Whyle finds to be “too thick” but still enjoyable. Whyle also spoke about how he used his skills as a television writer to write his novel, approaching it as a series of episodes out of which a much larger narrative was born.

Karen Jayes spoke about how her novel, The Mercy of Water, was inspired by her work in newspapers covering events in the Middle East when she discovered how, in various Middle Eastern locales, water was being used as a means of controlling people. It is part of the Middle East grand narrative which Jayes feels is not given enough coverage. Certainly, when speaking about the injustices, both against woman and against culture, in her novel, Jayes makes it clear that to think the topic of violence makes for impolite conversation is “a form of self-censorship that needs to stop”.

Karen Jayes asserts that to think it impolite to talk about violence is a futile act of self-censorship

Perhaps straying a little far from the session’s main themes, Madalie then turned the conversation onto the balancing act about both teaching and practising creative writing. Jayes made the interesting comment that creative writing seems to be an act of both “revealing and concealing”, with writers often hiding behind characters used to express the author’s opinions. This certainly seems to be the case in Boykey’s novel, Entanglement, which Boykey claims was the product of a “whiskey-fuelled fight at a dinner party”, involving what Boykey felt were dubious claims about a belief in levitation, beliefs that are held by people who, surprisingly, still remain the author’s friends. This ignited a “long, slow burn” inside the author, who holds a Masters in science from UCLA, and inspired a creative response which took the form of Entanglement. The novel’s protagonist, Jared Borowitz, is described by Boykey as an arrogant physicist having to endure a world of ignorance and superstition.

Boykey’s dinner party incident seemed to repeat on himself when, after questions were opened to the audience, a man stood up and made it clear that he was sceptical about Boykey’s scepticism about levitation. Just because Boykey had never witnessed an incident of levitation did not mean that it did not exist, the man argued. Cleverly, Boykey reasoned that just because he has never seen little green men on Venus does not mean they exist either. This was not the Sunday morning’s only incident of confrontation between a panelist and an audience member.

Imraan Coovadia says the debate about SA writing is now a 'frictionless' place badly in need of more frequent, sharper contestation, and a retreat from blind adoration of certain revered writer-figures

During the discussion, when Medalie asked Coovadia about his latest novel, The Institute for Taxi Poetry, Coovadia said he approached the novel as an “experiment”, one which he is yet to assess as a success or not. Coovadia said the novel was largely about the taxi world, which had never been “vividly represented” in South African fiction, and the satirically realised world of academia, which the author typifies as an area fraught with much “vagueness” and “frictionlessness”. Coovadia referred to an author like J.M. Coetzee, whose reputation and later novels are revered to the point that they are treated as “subjects of religion”. This he also finds true of Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country, which, while Coovadia certainly considers it an important and worthy novel, he also criticises for its inaccurate and flawed depiction of blacks, especially in Paton’s tendency to have his black characters speak in an alien King James Bible vernacular. This is despite the fact that the novel is now seen as an untouchable South African text. Coovadia called for “much more friction and much more contestation” when discussing, writing and teaching fiction.

However, an aspect of Coovadia’s comment did not sit well with at least one member of the audience. This particular person’s back was up because she had been already been overlooked when Medalie took questions from the floor. She appeared to take offence at Coovadia’s supposed ignorance in disbelieving that, as she claimed she could prove, many older black people in KZN still spoke in a kind of arcane English. She then accused Coovadia of “arrogance” and claimed that he was “quite intolerant”; he should step out his ivory tower and become more aware of people surrounding him.

Imraan Coovadia, who was roughly taken on by an audience member, in sharp talk with 'Boykey'

Coovadia responded by saying he always welcomed criticisms and disagreement from his students, but that too much tolerance created “vagueness” and we should try, therefore, to allow less of it. Anticipating a potentially over-long debate, Medalie quickly came to Coovadia’s defence by relaying his experience of teaching Paton’s novel for several years and finding that classroom discussions were much more productive when one has read the novel as a great but flawed text. Meladie also opined that there was a “hell of a lot that’s ridiculous about” (South African) works which we consider sacred. This last point provided some support for Coovadia’s other point about a lack of contestation when discussing canonical works, especially South African, that are praised with a kind of blind adoration, which, ultimately, stifles much of the potentially interesting discussion that may be had about these works. It is with these points that Medalie concluded the session.

Session 12 was a zappy occasion, and, despite sometimes straying from the key issues of war and transformation, some of the audience members’ confrontational demeanour meant that these themes were not altogether absent from the discussion.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

UCT is the only African university to appear regularly on lists of “Best 200” and “Best 500” etc. universities.

Not because of its English Department, perhaps.

Hi

I’m the person who took offence. Basically I made 2 points. One was that simply because Coovadia had never heard any Zulu people speaking using ‘arcane English’ did not mean it did not happen in the 1950s (not at present, please note). I gave examples of my own extensive interviews with 1930s mission educated people in Limpopo Province in 1989-1993, who did and still then used the ‘arcane’ English, with the general rythmns of Biblical expression. While there might be aspects of the novel that are in fact ‘ridiculous’, he seems to feel, along with Medalie, that understanding and situating a novel as a product of its time – I am an historian and a reader of literature and I thought that that was one of the ways one could approach a text – was akin to blind and uncritical reverence of the text, which rendered me incapable of any worthwhile opinions. I made a broader point that Coovadia does not really make an argument as such to debate. He relies on cheap shots and gross caricatures of Academia – of course based on some level of truth or they would not work. He described UCT as a third or fourth rate university based slavishly on the Oxbridge model. (I failed to say also that he presumably is paid by this substandard neo-colonial establishment, and has access to all its cheap imitation libraries etc.) I also challenged him to caricature himself – since he loves to do that to others, surely he would not be averse to taking a wry look at himself? (I think literary critics require a sense of one’s own ‘situatedness’ at some point in responding to a text.) I also said that I would be quite scared to take his course because I doubted how much actual debate within the creative writing centre would take place, given his position of power and prediliction for insult and generalisation. His furious reaction to my points simply demonstrated his own intolerance – very ironic since he seems to see tolerance as a sin akin to wimpy vagueness. In retrospect he reminds me of the great demagogue and intellectual bully Charles van Onselen, who presided over the African Studies Institute at Wits for 16 years, and constantly undermined people (including scores of unfortunate students and presenters at the African Studies Seminars) and his host institution with meanness and viciousness disguised as wit. I don’t think Coovadia comes even close, but then Van Onselen perfected his technique over a number of years. The second to last irony is that I think their writing is wonderful, with an extra-ordinary sensibilty, wit and compassion for the human condition. It’s a pity we have to actively separate the work from the person sometimes. The final irony is that Medalie and Coovadia both employed caricature of my argument as a response – in the time honoured tradition of what often passes for academic debate, but not always …

my poem about the event and the review is here on my blog:

http://lesfolies.posterous.com/good-work